Martha Cooper in Conversation

The famed photographer behind such quintessential documentary books as Street Play, Subway Art, and New York State of Mind talks about her early years in journalism, the inherent responsibility of making images, and her iconic work chronicling underground culture.

Martha Cooper’s biography reads like the field journal of a modern adventurer. Born in 1940s Baltimore, Maryland, Cooper first got turned on to photography by her father while in nursery school. After graduating early from high school, at the tender age of 16, she went on to earn an art degree from Grinnell College. She then joined the Peace Corps., where she taught English in Thailand before journeying by motorcycle from Bangkok to London, where she earned a degree in ethnology from Oxford. With such diverse life experiences under her belt, she settled in Manhattan, where she worked as a staff photographer for the New York Post in the 1970s.

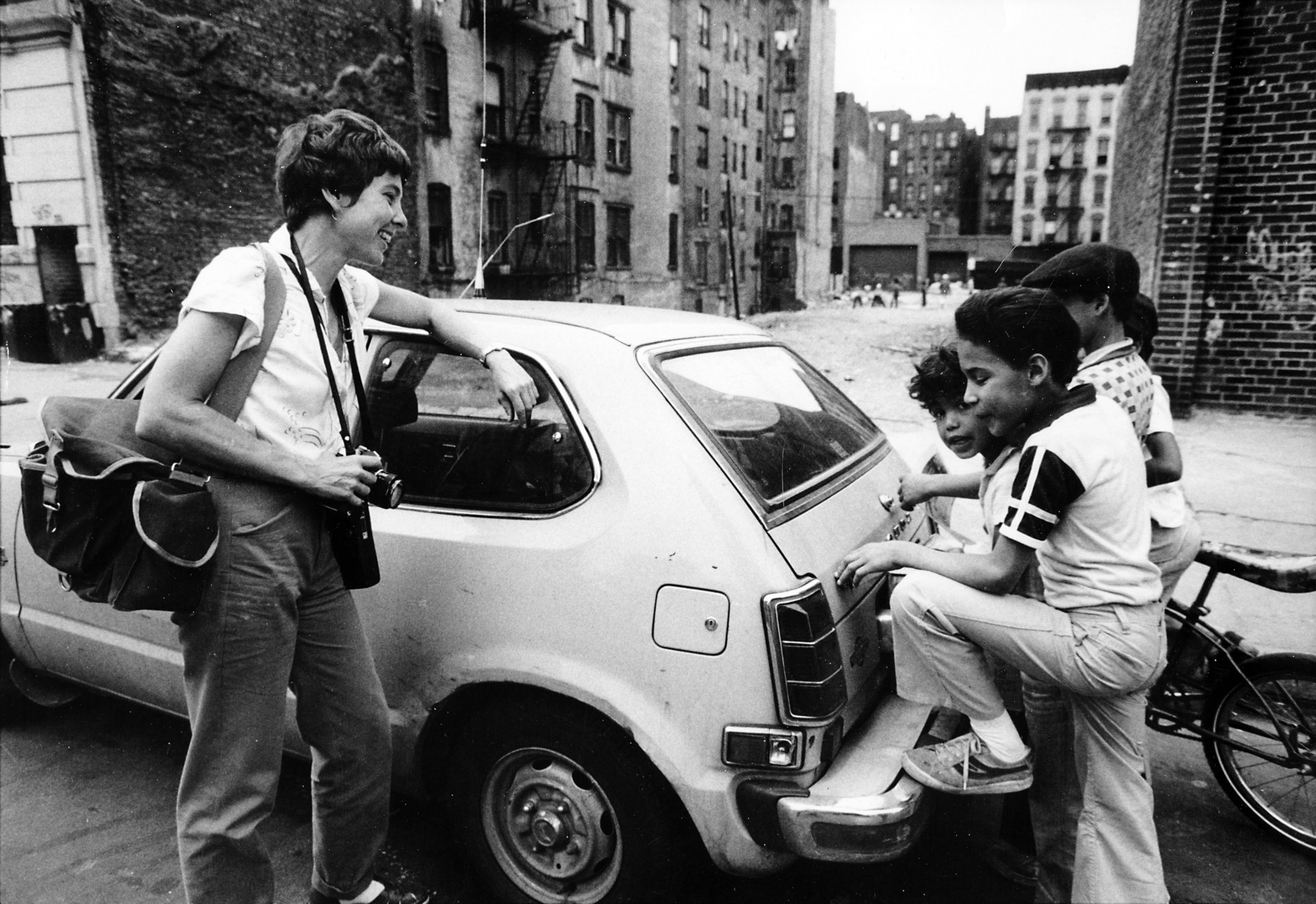

It was during this time, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, that Cooper started shooting some of the most famous photographs of her career. After work hours, Cooper began photographing children in her neighborhood, a personal project that soon introduced her to New York graffiti legend Dondi, who allowed her to photograph him tagging and painting pieces. Cooper then assembled the visual tome, Subway Art, a book that has become a must-read for anyone interested in graffiti culture. But what is often overlooked is Cooper’s astounding body of work outside of her graffiti and hip-hop photography. Her photographs of New York City life are beautiful and nuanced, like visual love letters to the people, places, and moments constantly in motion. And it’s this type of community focused work that keeps Cooper busy to this day. Her latest project finds her documenting the neighborhood of Southwest Baltimore, one of the worst open-air drug markets in the city.

You’ve been working as a photojournalist for over 30 years. What first attracted you to photography and what keeps you interested?

Make that over 40 years. My dad had a camera store and gave me my first camera when I was in nursery school so I grew up with cameras. Photography for me has been a way of preserving things I’m interested in. Publishing the photo has allowed me to share them since of course there was no internet for most of my life. By the way, I don’t really consider myself a photojournalist since to me the term implies someone who shoots news. I’ve never been much of a newshound.

Image from Street Play, Martha Cooper’s book on Alphabet City during the urban renewal of the late 1970s.

Photography is a powerful medium. In documentary photography, what do you see as the role and responsibility of the photographer?

There are many different, responsible ways to document with a camera. I admire people who attempt to expose evil , right wrongs, or engage in social commentary— however that’s not what I do. In general, I would say photographers should choose their topics carefully, treat their subjects with respect, and attempt to portray them accurately. Avoid the temptation to sensationalize an otherwise boring photo or story.

In the 1970s, you worked as a staff photographer at the New York Post. Can you talk a little bit about what that experience was like and how it compares with today’s media landscape?

Working for the New York Post, a major big city daily, was exciting, difficult, competitive, and lots of fun. It was not, however, a place where you could really dig your teeth into a story. The paper was heavy on crime and celebrities. It wasn’t unusual to have to spend a day outside the courthouse in the hopes of shooting (on film) some infamous criminal being escorted to his trial, or to spend a night at Studio 54 in the hopes of getting an exclusive shot of an elusive celebrity.

Originally published as part of Computerlove’s “Let’s Talk”

interview series in December of 2009.

Image from Street Play, Martha Cooper’s book on Alphabet City during the urban renewal of the late 1970s.

I enjoyed the fast pace of shooting something in the morning and seeing it on the streets in the afternoon edition. Today, of course, that sounds antiquated. There were no mobile phones, Internet, or even computers. Reporters used typewriters. We carried two-way radios with impossibly bad reception so editors could try to get hold of us for breaking news assignments. Since New York City is a media town, there was a lot of not-so-friendly competition between the dailies (Post, News & Times), news services (AP and UPI), and TV stations. I disliked always having to vie for a good vantage point.

Can you talk about your involvement with City Lore — the New York Center for Urban Culture? Are you still working as the director of photography?

I have worked with City Lore since its founding in 1986. It’s a non-profit cultural organization. Over the years I’ve worked on many projects with academics documenting everything from urban festivals to yard shrines. These photos have mostly been used as part of museum exhibitions or to illustrate articles in books and magazines. City Lore has been very supportive of my interests and helped me get grants to pursue projects of my own. The title “Director of Photography” is really honorary since I don’t direct much.

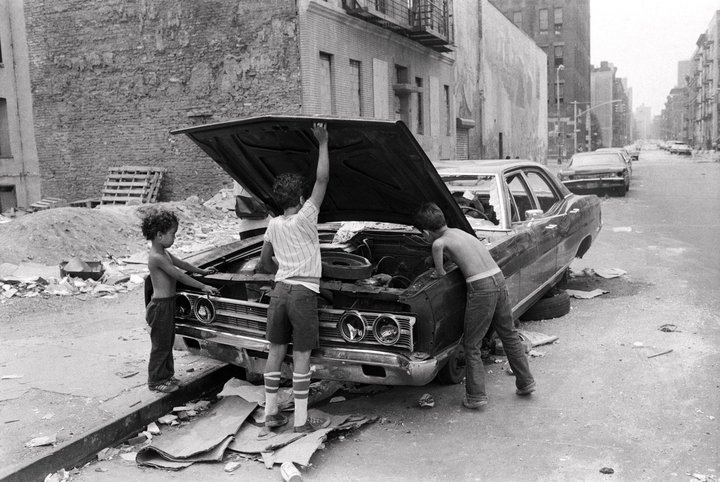

Image from Sowebo, Martha Cooper’s documentation of Southwest Baltimore, one of the worst open-air drug markets in the city.

You’ve been working on a photo project in your hometown of Baltimore. Are you at liberty to discuss the content and context of that project?

I decided that I wanted to try a long term documentary project outside New York applying what I’d learned over the years. Since I’m basically a street photographer, I wanted a place with a lot of street life. NYC has gotten very clean and corporate and I missed the edgy creativity of the Bronx in the late ‘70’s. I chose an neighborhood in Southwest Baltimore called Sowebo (after Soweto) and bought a very small house there in an effort to become part of the community. I take the bus from Manhattan every other week. It’s about a 4 hour ride south.

Sowebo happens to be near where my great grandparents settled in 1860 after emigrating from Europe. Today it’s known for being one of Baltimore’s worst (or best depending on your point of view) open air drug markets.

Your work documenting graffiti and hip-hop culture in its early days is both well-known and highly regarded. How would you characterize the evolution of these cultures since you first began your work?

I am in no way a hip-hop historian. My interest in early hip-hop began in the70’s with a project documenting creative things kids do when their parents aren’t watching. I never expected the art, music or dance to spread further than New York and I didn’t follow the evolution closely when it did.

Back in the 70’s hip hop was an underground culture known to only to a few. Today it’s the predominant worldwide youth culture. This means business people are trying to make money with hip hop and many of them couldn’t care less about its roots. On the other hand, now artists, dancers, rappers and DJs can get paid for their efforts and that’s great. I think there’s still plenty of creative stuff happening in all areas of hip-hop even if much of it has been overshadowed by the commercial.

With a diverse body of photographic work to your credit, what subject(s) would you love to tackle that you have, until now, been unable to pursue?

Right now my Baltimore project is as much as I can handle and I haven’t thought ahead to anything more. I need to spend some time working with photos I’ve already shot. However I’m keeping my eyes open.