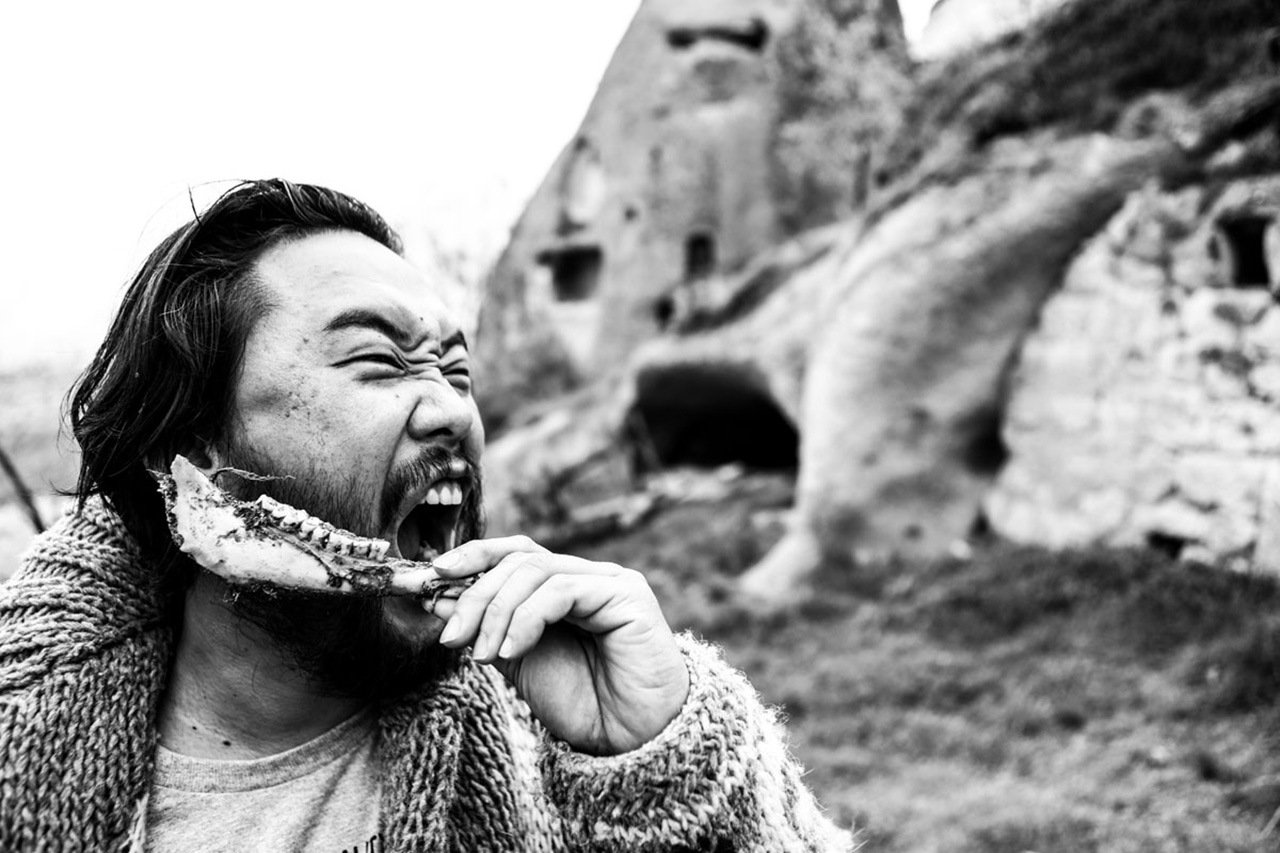

The Redemption

of David Choe

On the heels of his release from a Japanese prison, the Los Angeles-based artist talks about survival, vices, and his turn to Christianity.

For the better part of a decade, David Choe has perpetuated a fast and dirty style of art that captures—in frantic detail—the ills of a crumbling and decadent America. Images of sex and violence, heartbreak and despair—all infused with a dark sense of humor—are only a sampling of themes that permeate his work.

Born in Los Angeles, Choe now resides in San Jose, California, holed up in a downtown art studio that he rarely inhabits due to a severely overbooked schedule. However, that doesn’t mean you should pity the outspoken graffiti writer turned fine artist; the litany of dream projects currently consuming his time are the type that make under-worked creative types contemplate escapism via razorblade. He recently designed a monster truck for Scion, filmed a travel documentary for Vice, and exhibited in Barcelona with friend and graffiti legend Saber—and that’s only scratching the surface.

As of late though, Choe has focused his attention on the concept of redemption—not only in his work, but in his personal life as well. In 2004, after being arrested in Tokyo for assaulting a security guard, he was sentenced to three months in a Japanese prison. In the quiet of solitary confinement, Choe discovered Christianity, and set about making active changes in his life.

When did you first realize that art was something you had to pursue?

[My family] wasn’t poor, but we didn’t have much, so this started me down two very different paths to achieve the same goal: to get shit. The first path [was] art. Television influenced my earliest drawings. Since I knew we couldn’t afford toys, I’d try to draw my favorite He-Man, GI Joe, Transformers, and Super Friends on paper and cut them out and play with them. Since I knew they were gonna be my toys I tried to make them as real as possible.

The next path was crime. I started shoplifting. [however], in the last two years I’ve completely left the crime world behind except for three things: I still download music illegally; I ask for water at a [fast food] restaurant and get soda; and I buy one movie ticket and watch four.

Art wins out in the end. It was my first lover. I remember sneaking into the adult section of a magazine stand when I [just] started to get fur on my dick. My head was on fire from the images I saw. I ran home immediately and knocked over my Crayola box desperately searching for peach and pink—furiously trying to recreate what I just saw, and I started to touch myself from my own art.

My art has gotten me thrown in jail. It also saved me. When I [was] in jail and the Japanese thugs wanted to beat my ass, I would draw them like Asian Tom Cruises and I had new best friends. In Africa, when the village got restless, I hushed the entire tribe by spray painting…on a mud wall. Time and time again, it’s been my greatest asset.

You’ve mentioned making mistakes in your career, whether poor choices or misguided directions, can you elaborate on what you mean?

One of my art teachers told me, when I started school, he was like, “Alright, 99% of you are not going to make a career in art.” So of course you’re thinking, “I’m gonna be the one, I’m gonna be the one!” So, when I dropped out of school, this fear [was] instilled. [At first] I really felt like I was whoring out my [art] to things I didn’t want to do and working with people I didn’t want to work with, to like, further my career or whatever.

Now do you feel that you’re in a position to make better choices or that you have more freedom because there are better offers coming your way?

I feel like I’m the good looking girl that doesn’t really know that she’s good looking yet, so she’s sort of insecure [and] says yes to every guy that wants to fuck her. So now I know that I’m good looking and I’ve blossomed into whatever, so now I reject men more easily (laughing). I don’t know if that’s a good example, but… (still laughing). I think a lot artists do [the same thing]. A job comes your way and you think, “Wow, I may never get this opportunity again.” I still get jobs coming my way and I’m like, “I can’t believe I just said no to Pepsi,” but you get over it. Before, I was spread as thin as you could possibly imagine. I was saying yes to everything—every show, every job, yes, yes, yes, yes.

When you look back, do you feel like your work suffered?

That’s the thing, I still feel spread thin because I [can’t] catch up with myself. I [recently] showed up to Barcelona for an art show [at Montana Spray Paint’s gallery] with nothing, three days [before the opening]. It’s almost like it turns into a game then. The stuff I spend a long time and labor over, people appreciate. But the stuff I do really fast and recklessly, that’s the work people respond to. …I don’t know if the work really suffered. There’s something inherent in me…I’m used to doing stuff that’s illegal. Like, if I’m doing graffiti, I’m always trying to do it as quick as possible. If I’m in a gallery, obviously no one’s going to tell me to stop, but I have this weird [feeling] that someone’s peeking over my shoulder saying, “Hurry up, hurry up.”

Working at such a fast pace is the challenge more in keeping up with the ideas as they’re popping into your mind, or do you normally just have one main idea and build from there?

No man, it’s always so scatterbrained. The mediums I use are always different. And that’s the thing—and nothing against all the artists out there right now that are character-driven artists, that are sort of like the one trick pony—for me personally, I want to be the master of every single medium. And if there’s a new medium that I don’t know about, I want to get on it right away. This is where I excel. I may fail at everything else in life, but this is what I want to be the best at. You said it perfectly, I feel like I can’t even keep up with some of my thoughts sometimes.

Did the success of Slow Jams and the exposure of your artwork to a larger audience help segue to gallery shows and other new opportunities?

Exactly, people wanted this comic even after it sold out. There were tons of people writing me, and I thought, “Wow people are really responding to it, they really liked it.” Then, [after] figuring out what it takes to actually be a comic book artist, like, “Do I have the discipline to do that?” Absolutely not (laughing).

If you’re a comic book artist, you have the worst posture, you’re going to be paler than a ghost, you have no social life—I’m talking about if you’re going to be a good one. It just takes so much energy, especially if you’re writing it, and drawing it, and then self-publishing. The thing is, I wrote Slow Jams when I was probably 19. Then I wrote Slow Jams Part 2, which has been sitting in my desk for over a decade, when I was like 21. Writing is so easy for me because I just puke it out. [But] to draw and render it, I know what that’s going to take. So I’m like, “I’ll get to it one day.”

I wonder then, how do you view your evolution as an artist since that time?

At the beginning of all this, I was acting out and angry about all the shit you should be angry about when you’re a teenager. Rejection was a huge part of building [my] character as a person. The fact that my art wasn’t [initially] accepted [and] getting the door slammed in my face at every gallery really sucked. All the rejection…the “Whatever doesn’t kill you just makes you stronger” feeds a lot. It’s a huge driving force—the drive to not fail.

Do you feel that instinct still drives you now?

Yeah. I still have this unquenchable thirst to create. I’m about to put out this 10-year, 500-page [retrospective] book, and I just look through it thinking: “This doesn’t even feel like the tip of the iceberg for what I have inside me.” I just feel like there’s so much I haven’t even begun to explore yet. And that gets me hard, that gets me excited, I can’t wait.

Your style is constantly evolving, but it seems graffiti is always a definitive undercurrent. How has the role that graffiti plays in your work changed over the years?

I never stopped graffiti; it influences my fine art, with the quickness and immediacy of it. I use oil paint like it’s acrylic, because I can’t wait for it to dry. I love fucking with mediums and see how they react to different mediums, but I always considered graffiti separate from my art. I always looked at it as destructive, anarchist, political, spiritual, and mostly just fun. It was a release from being cooped up, hunched over drawing tiny drawings with rapidographs and mechanical pencils. Fuck everything I’m doing at home, I‘m going out late at night to have an affair with the streets.

I‘m not worried about mistakes or trying to make shit look right, or fame, or writing a tag over and over; I’m looking to destroy, pure vandalism, and maybe somewhere in between the process I can achieve enlightenment, fulfillment, and redemption, but probably not. You can’t ever really describe the feeling until you’ve stolen two cans of Krylon flat black and hit the streets with reckless abandon. The freedom of speech, and scale of the words and pictures, is humbling. I just got back from the original Montana spray paint factory in Spain and they’re gonna give me my own color; I creamed my pants. All my ridiculous childish porno graffiti cartoon dreams are coming true everyday. Everyday is a blessing.

As for all the mixed media, it started from just being experimental and having no attention span, but I guess my views on this are sort of old school traditionalist, but I just think if you want to call yourself an artist you shouldn’t be limited to mediums, your comfort zones, or whatever. You should be able to master every medium, and be able to create great works of art in any situation, time, and place, but that’s just me.

I read that while you were in prison in Japan, even though you felt it was so cliché, you talked of finding God in that experience. Now that you’ve served your time, how does this discovery fit in to your everyday life?

It’s really hard. I tell a lot of religious people about it…they say no matter what traumatic experience you go through, you will be back to exactly the same person you were three months later if you don’t make active changes in your life. I still struggle with religion. If you’re a junkie or drug addict or alcoholic and then you [relapse], it’s out of sight, out of mind. But if you tell people you’re Christian, they will never let you forget.

How have your longtime fans reacted to your Christianity?

It’s super hard. The first question after I got out of jail, from everyone was, “How is this going to change your art?” I feel like my art is disgusting and sick, and I feel like everyone has that evil disgusting creature inside them, I just want to get it out. It’s almost like an exorcism for me. I just want to draw it and get it out of my system. Is that okay, is that proper for someone who says they believe in God to do something like that?

I was looking at your prison art and was struck by the notion of working in that environment. How did those paintings and illustrations come about?

I had at least 10 nervous breakdowns while I was in prison. I’m a fucking beast; I can’t be caged like that. Once my lawyer told me I was possibly looking at two years, and I was in a tiny cell for months in solitary confinement, killing myself started to enter my mind no matter how hard I try to keep them out. Also, I started to get hornier than I had ever been In my life, while I knew in the outside world my life was also falling apart. To keep myself from focusing on how to solve the riddle of killing myself, and beating my dong into raw hamburger meat, I needed to escape, so I started to render these fantastic sci-fi worlds that I rendered the shit out of.

Then I just put them against the wall, laid on my side, and stared into them and fell into the pictures to escape. Prison brings all your ills and sickness out, my hair started to fall out so I started tying all my fallen hair into tiny little knots; it killed time and it looked like their were tiny spiders all over my floor. The day I washed my jeans in the sink and realized I could get blue dye out of them, I started crying and screaming like a maniac, ”WE HAVE BLUE! LADIES AND GENTLEMAN, WE HAVE A BLUE! LET’S HEAR IT FOR THE COLOR BLUE!”

I drew and wrote so much my fingers throbbed and cramped every night. I wrote a 1,000-page outline for a sci-fi porno end of the world novel; the finished book should push 10,000 pages. I drew pages and pages of naked women doing disgusting things, I mean beating the shit out of each other. I drew the guys in my holding cell from the first month as characters from Lord of the Rings and they beat the shit out of each other to see who got to keep it. When I was in the holding cell, we only got one pen to share between five guys every other day for only four hours, so when it was my turn, I had no choice whether I felt like it or not; I drew and wrote as much as I could. Only when I got to solitary did they let me buy my own pens. I had one red pen, one black pen, one pencil, and when I started to fiend [for] painting, I used soy sauce from breakfast; for the brush I used the tip of my sock. Months later I started to use my own urine for the paint and my cock for the brush. It’s the same story repeating—the art saved my life.

This interview originally appeared in the January 2007 issue of Juxtapoz.

Photograph by Estevan Oriol